Burlison & Grylls

I have only a few weeks left at the Prince’s Drawing School and it is dawning on me that the summer is going to bring with it the daunting process of working out where to go next. It’s not as simple as sitting around playing with paint and prints, as I’m the kind of person who needs vision, projects, deadlines, and dare I say it, a brief. I need purpose, and I often wonder how much scope there is for ‘jobbing’ artists today, in a world which seems very divided into ‘fine’ artists, illustrators, designers and their numerous sub-divisions. I wish I’d been born a century earlier, so that I could have never fretted about a career, but gone straight into the family business designing stained glass windows with my ancestors Thomas John Grylls (1845-1913) and his son Harry Grylls (1873-1953). Of course, being a woman I wouldn’t have had the right to vote or probably own property in my own name. But I like to think that I could have been apprenticed at 16 and worked my way up, visiting churches and cathedrals that were being ‘restored’ or newly designed, spent mornings researching fifteenth-century imagery in the British Museum and afternoons sketching and scaling drawings into Gothic Tracey before bringing out my watercolours. I doubt many clients would have wanted to deal with a woman, but all the better for spending more time in the studio getting on with the creative side of business.

In 1868, the Gothic Revival Architect G.F. Bodley was getting a bit bored with Morris & Co’s stained glass designs. Their lead artist, Edward Burne-Jones, was heavily into his Italian Renaissance-inspired style, which just didn’t suit Bodley’s own north-European Medieval style architecture. So Bodley encouraged the 23-year-old Thomas Grylls (the main designer) and John Burlison (the business man of the firm), to set up on their own firm. Thomas was well-trained in churches, his father having worked for Walkers, the organ-makers, and was apprenticed to the well-known firm Clayton & Bell from an early age. Burlison & Grylls went on to designed thousands of windows all over the country in the next century, and even shipped designs to America, South Africa and New Zealand.

It’s an opportune time to find out more about the most note-worthy jobbing artists in my family history, the prolific, though not widely known Burlison & Grylls. My father has been compiling his own database and photographing windows for years and has built up an impressive collection, some of which you can see here. Last week we visited the Victoria & Albert Museum, accompanied by the lovely Dr Ayla Lepine, a passionate academic and self-confessed nerd on all things Gothic-revival, to see some of Thomas and Harry’s designs. As what might have been any kind of archive was destroyed by the Blitz (the firm’s offices were around the corner from Oxford Street) this is the best surviving selection of drawings we know of (if any churches just happen to dig some out, let us know!).It was extremely exciting to gently lift out each picture, illustrated in pen, ink, watercolour, from their archive boxes. With each new picture came a new round of ‘oohs’ and ‘ahhhhs’ from the three of us. The colours looked as fresh as if they had been painted yesterday (on a personal note reassuring to me as I use watercolour so much). Virtually all save the last two were made at a small-scale, and so are schematic designs for client approval. The end designs sometimes changed, if a client developed a clearer idea of the iconography they desired, or the artist was able to refine and improve his design as the manufacture of the window progressed.

Here’s a selection of photographs reproduced by kind permission of my Dad.

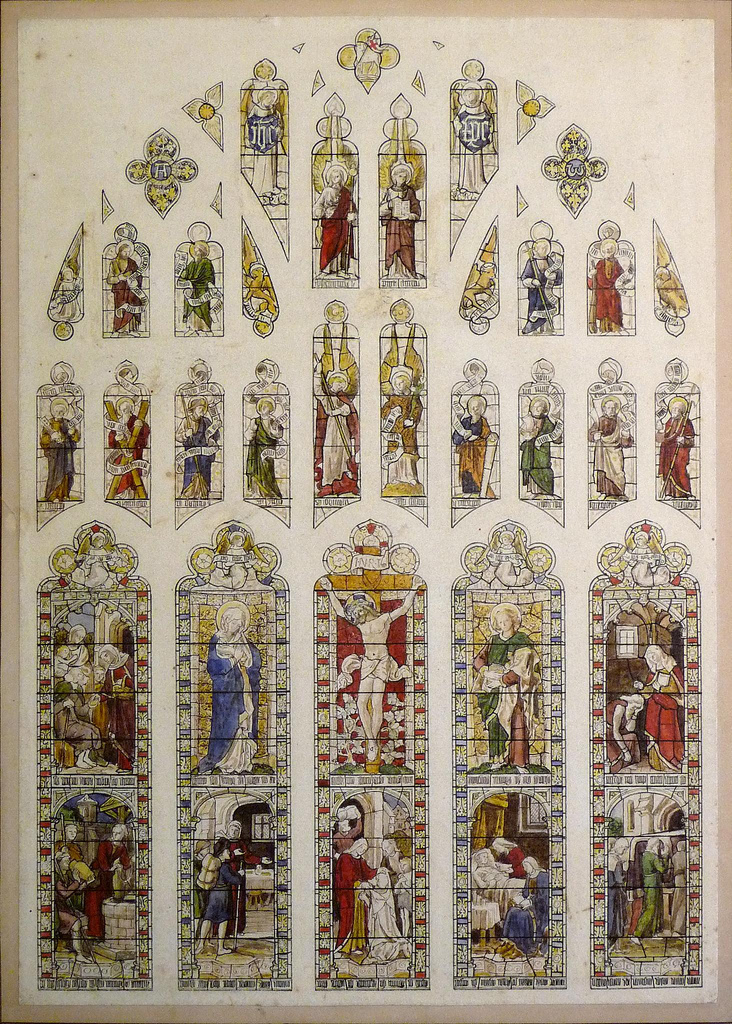

Cartoon for East window, St Matthew, Walsall.

Crucifixion tableau. Side and lower lights: Seven Corporal Works of Mercy. Upper tracery: four archangels, flanked by the four evangelists and symbols, and lower row of Apostles.

Burlison & Grylls, c. 1880.

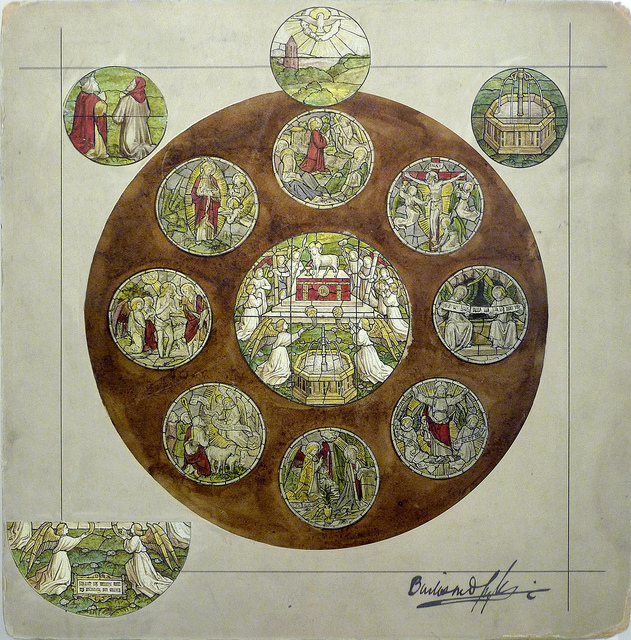

Cartoon for St Paul’s Cathedral.

A seraphim, set within renaissance frame, with swags and cherubs.

Burlison & Grylls, 1890.

Cartoon with varied designs for SS Philip and James, Oxford.

The Adoration of the Lamb, after van Eyck

Burlison & Grylls, 1912.

The finished window (as photographed by Eric Hardy)

Interestingly, the completed window presents a multitude of figures, angelic hosts, saints and fathers of the Church, in attitudes of adoration in the subsidiary roundels, thereby giving considerably greater emphasis to the central theme of the window.

Cartoon for St Matthias, Malvern Link.

Burlison & Grylls, 1906.

Left: St Peter’s vision of ‘the great sheet’ at the house of Simon the Tanner, Joppa (Acts 9:43ff), where the soldier, messenger from the centurion Cornelius, finds him. Right: Peter comes and preaches salvation to Roman centurion Cornelius, the first Gentile convert, and his family (Acts 11:14).

On top of the dramatic and theatrical perspective, we especially liked the blanket of animals on the left panel which looked like they could have been lifted straight from a late medieval illumination.

Cartoon for St Mary, Greenham, Berkshire.

War Memorial window. The soldier knight, beneath angels bearing a crown, keeps vigil before the altar

Burlison & Grylls, 1924.

The completed window set within a memorial chapel.

I have an enthusiasm for war memorials from the days I gave tours of them at the Twentieth Century Society. This was exciting to see, the design a concept of a chapel within a window within a chapel. I was also interested to see how the finished soldier had a later style of armour that is more decorative, elegant and with a streamlined helmet.

Section of full scale painted pattern for an unidentified window.

Lower section of a Crucifixion tableau: Mary Magdalen embraces the foot of the cross (her jar of ointment is out of view below)

Burlison & Grylls, n.d.

We were bowled over when this was carefully rolled out by the V&A staff. So sad that bits were literally falling off at the edges. But after a morning looking at small-designs, to see this design made at 1:1 was stunning, reminding us of the impressive draftsmanship and ability to plan the leading of windows so carefully.

Full size and painted pattern for an unidentified window, depicting St Augustine.

Burlison & Grylls, n.d.

A great finish to a great day. Thankfully this picture was in great condition and huge, so we could really enjoy looking closely at the details that both Grylls men so enjoyed drawing themselves and the firm were known for. As with most of their windows, the face and hands receive the most careful attention. Sometimes this sensitivity can feel lost when completed in a finished leaded window set high in a wall, which has the sun’s bleaching rays coming through and a host of competing colours, architectural details and patterns around the figures. But it is deliberate, for it is the nature of their work across thousands of windows and I think that it’s a very interesting way of working. The viewer has to look a little harder, work through all the decoration and graphic contrasts, and somewhere in the middle focus on the faces. It is stimulating artistically, and importantly, devotionally. And they’re incredibly human and rarely idealised, sitting somewhere between the realistic animated characters of Northern Renaissance art (inspired by Albrecht Dürer and his contemporaries) and real Victorian and Edwardian people, that we know both Grylls men used, as models.

Thank you so much to the staff at the V&A for putting up with our gushing in the otherwise silent study room, to Dr Ayla for her encouragement and insight, and to Dad for making me feel part of a family tradition of drawing (and for the yummy lunch).

After the adrenaline of the day’s visit subsided, I couldn’t help but feel rather emotional about it all. As an artist starting out it makes me so excited to think that such ability runs through my genes. I am so encouraged by the sheer beauty of some of their designs (for the completed windows in all their glory, browse here) and prolific output as artists and designers that it makes me want to aim higher for myself. But, I also balance some blues and intimidation when I consider what a high standard of design, and professional success, is embedded in the tread of the footsteps I follow. After being brought up with trips to see windows (no family holiday was complete without ducking into a church) it means so much to see the original designs on paper. All the more moving to see that the Grylls father and son were, like me, driven by draughtsmanship and delight in detail and light. So even though I never knew them, I feel I can still converse with them and learn from them every time I see a window.

Your great-great-grandpa was no fool, he had his female apprentices (though there was probably no question of ‘apprentice indentures’ or a pittance wage) as several of his 10 daughters were ’employed’ in helping him, both as artists (particularly Dolly and Kitty) and as models. And he may have had help too from the Burlison side, as Frances (Bessie) trained as an artist. Agreed, it was a great and very moving morning.

Lovely windows, and very interesting history!! Any relation to H.J. Maxwell Grylls, a British-trained architect, who in 1907 joined the Detroit MI USA architect firm of Smith and Hinchman? See this page for more on their history: http://www.smithgroup.com/?id=1427

Jo – loved the post. Incredible to think you have all that artist’s blood running through your family!

I also am interested if there is a connection between Mr. Grylls of SHG in Detroit and the British stained glass firm. The Fall issue of New England Historic Gen. Society has a stained glass window (maker not indicated), but contacting UK stained glass colleagues, they have documented the church in Boston, UK and the window in question is by Burilson & Grylls. I am sending a Letter to the Editor for their Winter issue to detail this woman’s visit to V&A and the relationship between people ancestry and that of stained glass.

The church referred to is St Botolph, Boston, Lincolnshire, where there are four windows by our great-uncle Harry Grylls, from his later years, dating between 1938 (Cotton Chapel) and 1948.

The Cotton Chapel window is perhaps the best known, quite dramatic: there is a photograph of it at http://www.flickr.com/photos/8118630@N08/6113224485/ and the same photographer has also uploaded several detail photographs (insert ‘Boston’ on the search button on his flickr site) from the same and other Grylls windows. There are several interesting connections between Cotton and Massachusetts depicted in the Grylls windows in the church, including John Cotton and his congregation wishing farewell to his parishioners departing on the Arabella for New England in search of greater religious freedom (he later emigrated himself), and the American Ambassador attending the reopening of the chapel in 1857.

There is no direct familial connection between our particular branch of the family (the Burlison & Grylls connection) and America; however, if you wished to contact me directly I could put you in touch with Richard Grylls, a genealogist who has researched vast swathes of Grylls descendants and who may well have information on American branches.

Hello – If there is no known relationship, then don’t ask anyone to take the time to research….thanks anyway, not that importatn….BUT, are there any known Burlison & Grylls windows in the US that I could refer to in the reponse I intend to send to the mag?. You may be aware that many/most stained glass windows in the UK are being scrutinized as to the maker/artist, studio, etc…..Margaret Washbourn was the person who told me about the windows in question. I have come to several BSMGP conferences….the publication: Stained Glass Marks & Monograms is what she was involved with, and there is mention of your relative’s firm and some windows have been signed (when I looked the first time apparently 2 pages stuck together and I missed the notation…..

Hi, for your information I’m currently cataloguing the work of Burlsion & Grylls, trying to pull together all the various sources into something more authoritative, obviously referring to the work done by Margaret Washbourn, Alf Alderson, Robert Eberhard and others. I hope eventually to publish my database: until then you’ll find a lot of B&G images on flickr at my photostream http://www.flickr.com/photos/99168983@N00/ and in our group http://www.flickr.com/groups/1108003@N21/. As far as the US goes, so far we have records of 4 windows in Trinity Episcopal Church, Boston, Mass. and 1 in St Paul’s Episcopal, Stockbridge; then there’s 1 window in Grace Episcopal, New York, 1 window in St Martin in the Fields, Philadelphia, and 1 window in Torresdale. What images I have of these you’ll find at http://www.flickr.com/search/?w=99168983%40N00&q=usa. Obviously I would always be grateful for information and images of any other windows in the US. Best wishes.

I’m cataloguing Church windows in Guernsey, C I . I’ve found two by Burlison & Grylls so far, but there may be others, have you any listing of their works in the Channel Islands?

Hello

I am at Buckfast Abbey in Devon. Pevsner lists the West windows, Porch window, north & south Transept windows and Sanctuary windows as all being the work of Harry Grylls. Style: late 12th century —- can anyone con firm this information?

The West window: Madonna & child & scenes from the infancy of Christ

Porch: four evangelists (one destroyed by vandals & replaced with modern)

N.transept: OT prophets, Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Elizabeth and Simeon, Abraham & David.

S,.transept: Winfrid (Boniface), Petroc, Andrew & John Baptist

Sanctuary: Sts.Peter & Paul, Trinity & Pentecost.

Fr.Thomas Regan OSB

Of the windows in the church of which I am rector, St Michael and All Angels, Observatory, Cape Town, South Africa, there are quite a number by Burlison and Grylls. In the Nave there are a St Peter and a St Andrew (circa 1899). In the Lady Chapel there is a three light Virgin with Child with shepherds and magi (dedicated 24 December 1910 – what I think is the best window we have) as well as three windows – Faith , Hope, Love – dedicated Ascension Day 1912. In the sanctuary there are three windows – The Ascended Christ, Angel in blue robe and Angel in red robe – dedicated Michaelmas 1907.